| From The Garden of Ed. Submitted for publication in The Towne Crier on May 3, 2006

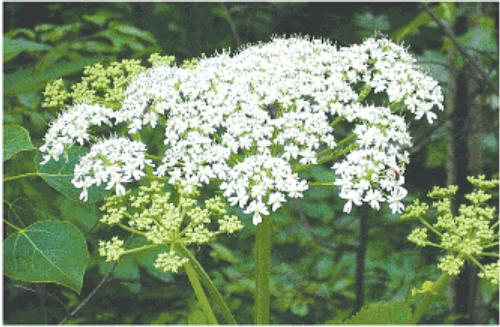

Botanical Miracles or Botanical Curses? Weeds may be many things to many people. It all depends on what kind of hat you are wearing. The "hat" thing is a lot like walking in someone else's shoes.  Wearing a photographer's hat, I see untold opportunities to explore and express the wonder and beauty of the natural world. To expose the glorious splash of gold of the lowly Taraxacum officianale, the underappreciated Dandelion blossom, or, raised to another level, the exquisite architecture of its seed-head, the hints of both death and rebirth, could not be more eloquently displayed in the view of the sensitive camera handler. This same is true of our Queen Anne's Lace, or countless other (what we call) weeds. Wearing a photographer's hat, I see untold opportunities to explore and express the wonder and beauty of the natural world. To expose the glorious splash of gold of the lowly Taraxacum officianale, the underappreciated Dandelion blossom, or, raised to another level, the exquisite architecture of its seed-head, the hints of both death and rebirth, could not be more eloquently displayed in the view of the sensitive camera handler. This same is true of our Queen Anne's Lace, or countless other (what we call) weeds.

When I don the hat of the home gardener, however, a different set of values and emotions comes into play. One of the things that stand between the harvest and the harvester is the weeds that can greatly impact on the quantity and quality of the harvest. Research studies indicate that regularly weeded plots of carrots and onions yielded 20 to 30 times, beets and tomatoes 5 to 7 times, and cabbage and potatoes 2 to 3 times more than their weedy counterparts. Hand pulling, hoeing, and regular attention are the requirements to achieve the best numbers. It's about sweat equity. Wearing a tam-o'-shanter and assuming all the responsibility of the St. Andrews 18 hole world class golf course, I would be deeply enmeshed in weed elimination. My job would rest on it. The budget for weed control is huge, as it is on most golf courses worth playing. The weed control products themselves are from the petroleum industry and prices are constantly on the rise. Needless to say, the number of companies that supply myriad chemical formulations to control and eliminate weeds in lawns (an America pre-occupation) and vast expanses of turfgrass are legion and in strong competition. Their budgets burst to supply effective products that will maintain healthy, weed free conditions on lawns and golf course tees, fairways, roughs and greens so the landscape manager and the above-mentioned superintendent keeps his employer and his clientele happy. This same endeavor employs a cadre of soil scientists, weed specialists and chemists striving to supply new formulations to compete in a thriving weed control industry. There are weeds that are notorious for fouling ponds, clogging culverts, and polluting lakes and streams. They are aquatic plants trying to survive. But, they impact on the health of the living occupants of these bodies of water. Fish and other wildlife suffer and perhaps die. Recreation is impaired. Much effort and money is spent trying to outwit or overcome the algae and other aquatic weeds. Only a few weeks ago I mentioned the wealth of edible wild foods available for the taking or cultivating. That lowly dandelion is rich in iron, vitamin C, vitamin A, and potassium. It is used to make a coffee substitute, wine and has many medicinal uses. It may surprise you to know that upward of $3.5 million dollars are spent by Americans purchasing the greens for food and other culinary uses. (You'll see them at Farmers' Markets). As many dollars again are spent on dandelion products that are used for medicinal and herbal remedies. All parts of the plant feed a variety of wildlife, too. A large array of other weeds serves man and beast in many similar ways. The economy is nudged this way and that by the success or failure of weeds. Some weeds have the ability to irritate the skin, and others, to put some into the hospital. Their toxicities are variable depending on the subject. Even the poison ivy treatment industry is substantial. Livestock are at risk from ingesting toxic plants that found their way into the field. The weeds that a farmer does battle with can seriously impact on his crop's success. He might suffer great loss of product, or he might have to invest heavily in herbicides. The bottom line is affected. Not unlike the golf course superintendent's profit picture. Weeds are an economic 'force majeure'. Crafts people rely on many weeds for their finished product, be they fiber made, fabrics dyed by natural processes, dried arrangements, or pressed flowers for framing. Look around. Many industries both great and small revolve around the presence or absence of weeds. Weeds provide a valuable service to the overall ecology. Because they are such opportunists, they colonize bare ground with relative ease and protect our soils from erosion. They provide home to a variety of surface and sub-surface animals as deep as several feet thanks to the penetrating ability of their roots. These same roots help transport elements from the subsoil to the surface improving fertility and drainage. Some weed roots can penetrate the soil to depths of twenty feet. Soil scientists, ecologists and botanists are accustomed to seeing weeds as important indicator plants. A specific weed might provide clues to the presence, absence, or quality of water, trace minerals, soil pH, and nutrient content. Some weeds thrive in soils of very poor fertility. Others only thrive in fertile soils. Some in sandy soils, others only in clayey soils. Some dry, some wet, and so forth. The more we know about weeds, and what each one's presence indicates, the better equipped we are to manage our soils wisely. Perennial weeds tell us more than annuals, because they have been present for more than a year. Likewise, communities of weeds tell us more than a single species. The strength is in numbers. Even if you've never read "A Tree Grows in Brooklyn", you likely have heard about this popular novel of the forties. The metaphorical tree is the Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima, an alien tree, and a very successful weed growing to eighty feet. It is so successful it grows between the cracks of concrete, ascending surrealistic heights, and eventually cracks and breaks apart the concrete in its struggle to continue to dominate its conditions. This brings me full circle, to ask (rhetorically), "What is a weed?" As you might now gather from all the above, I might define a weed as: a photographer's glorious subject for study, a bane of a home gardener's efforts, a golf course's big budget item, the agro-chemical industry's new priority, an underrated human food source of high nutritional or medicinal value, a craftsman's raw material, a major player in a farmer's economic outlook, a subject of an entire branch of science and industry, any grower's indicator of soil composition and quality, a delivery system of poison to the uninitiated individual citizen, homeowner, gardener, and farmer. It is often said that a weed is a plant growing where it isn't wanted. That is to say, a plant growing out of place. To the degree that they pose a threat to man's activities, his economic gain, or his overall welfare, they are called "pests". To this same degree, they are dealt with using organic or chemical "pesticides". They have become the "enemy" that needs to be controlled, regulated or eliminated. Strong words that fly in the face of all the benefits mentioned so far. Sometimes necessary steps need to be taken. Depending on what "hat" you are wearing, weeds are known as noxious, wicked, invasive, tenacious, pernicious, dinner, medicine, curses, beautiful, food source, culprit, wildflower, botanical wonder... I could go on. I think you get the gist of it, yes? A weed is a plant. It has as much right to live as its competition. Or not? You decide. It depends on your "hat".

From The Garden of Ed. Submitted for publication in The Towne Crier on May 3, 2006

© 2006 Ed Mues. All Rights Reserved.

eMail: eGarden@MountainAir.us

|

|